When was the last time you used your park brake? During a training seminar recently filled with brake people I got a lot of blank stares. Ok, rule number one don’t ask open ended questions right after lunch. Rephrasing, how many of you used your park brake when you parked the car today, one hand went up. You drive a manual transmission, correct! OK, you don’t count.

How many have used it in the last week? Zero. How many in the last month? One hesitant hand rose. In the last six months? Two or three more hesitant hands rose. OK, I made my point; nobody uses their park brake, at least in the midwest. So, if nobody uses it, why do vehicle manufacturers insist on having one? Well the simple answer is, it’s required by law.

How many have used it in the last week? Zero. How many in the last month? One hesitant hand rose. In the last six months? Two or three more hesitant hands rose. OK, I made my point; nobody uses their park brake, at least in the midwest. So, if nobody uses it, why do vehicle manufacturers insist on having one? Well the simple answer is, it’s required by law.

Section S5.2 of FMVSS 135 (Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard) states: Each Vehicle shall be equipped with a parking brake system of a friction type with solely mechanical means to retain engagement.

OK, knowing that Big Brother says we need one, what must it be capable of doing? Summarizing the Performance section of FMVSS 135: The Park Brake System must be capable of holding the vehicle stationary on a hill, specifically a 20% grade. The vehicle must hold the hill pointed up and down and it must hold the vehicle at its maximum loaded condition otherwise known as GVW or gross vehicle weight. It must hold the hill by not requiring more force than 400 Newtons (89.9 lbs) for a hand applied brake or 500 Newtons (112.4 lbs) for a foot brake. Lastly, the vehicle must hold the hill while being in neutral.

So considering these minimum federal requirements what are some of the considerations and alternatives that appear on the market.

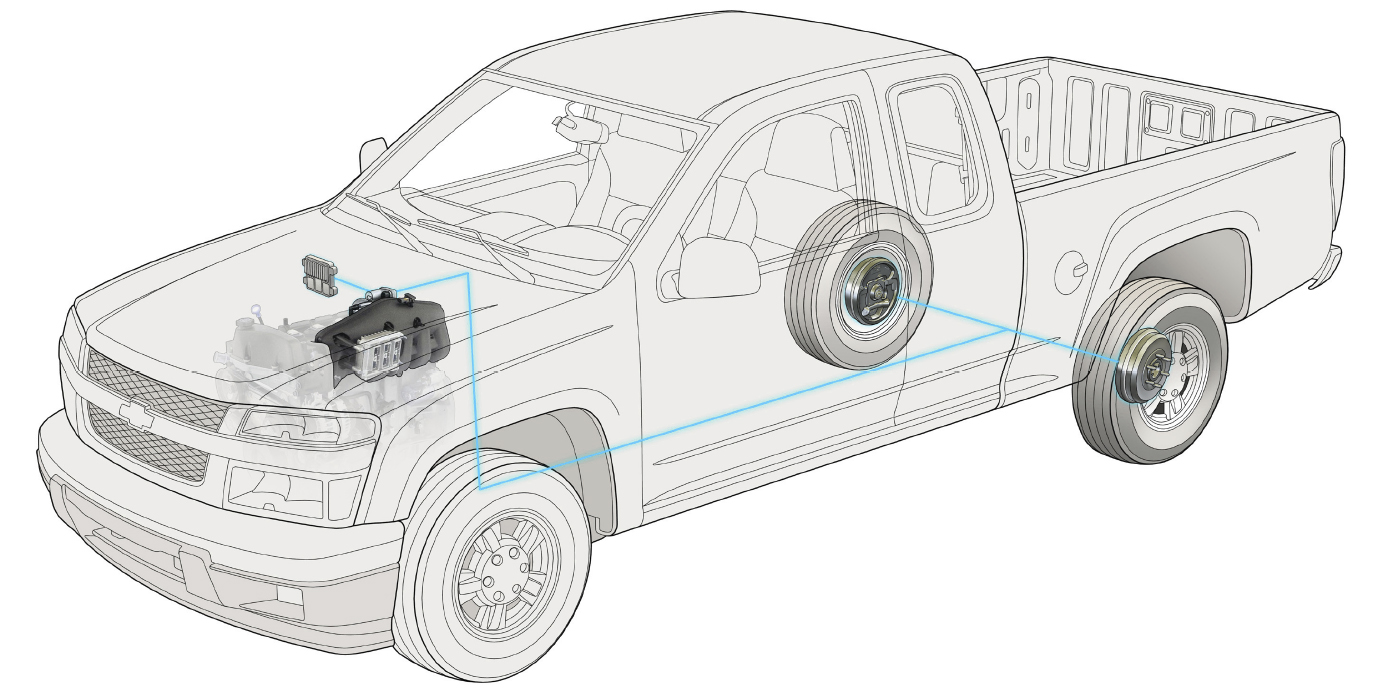

First of all the parking brake is a system. It exists largely in parallel with the primary brake system and will use some of the components of the primary braking system. In most cases, there are three primary sub-components in the park brake system.

The Apply System (the pedal or lever assembly)

The Transmission System (the cable system)

The Torque Generating System (The brake that holds the vehicle)

The first decision that must be made when designing the park brake is whether it will be a foot pedal or a hand lever. This decision is really an interior styling issue and generally not made by a brake guy. Generally, trucks and larger vehicles have the foot brake and smaller vehicles have a hand brake in the center console someplace. Occasionally, the lever will be placed on the left side of the driver between the seat and the door. This is seldom done due to the added complication that the lever must be able to retract without disengaging the brake so the driver can exit the vehicle without hanging up real important stuff on the way out.

The next decision that must be made is the manner in which the brake will be released. There are a lot of choices here. The most common is either a release button built into the handle or a release handle mounted somewhere near the bottom or under the lower dash. Some are integrated into the dash and again the styling guys enter the picture. Sometimes a nice black handle makes for a nice contrast to the dash color and sometimes they want it to match. In this case the release lever must now be colors such as cashmere or dirty linen.

If the preference is not to have a driver-controlled lever release, then a few other options exist. Push to release requires the driver to push on the pedal again to release the brake. Some release mechanisms are integrated into the transmission and when the vehicle is put in drive, a vacuum or electric solenoid triggers the release of the brake.

Most of these decisions are not really technical in nature and are really drivers and styling preference. The key performance aspect of the apply system are the lever ratio of the pedal or handle as this determines how much force you will send down the line to the brake. This also determines how much travel will be available to actuate the brake at the other end. Remember, force and travel are tradeoffs with a lever so if you want more force multiplication, you better be able to live with less travel.

The cable system then carries the force down to the wheels. Packaging the park brake cable system the length of the vehicle is one of the most thankless jobs in the engineering of a vehicle. The cables must worm around everything else. They can’t rub or touch anything, shouldn’t droop down into sightlines or catch on stumps either. As all the other stuff in the vehicle jockeys for its final position, the cable is always the part that will be told it has to move to accommodate the other parts. The environment of the cable is brutal. It see’s all the road conditions — mud, salt, water, ice and rock. Therefore the cable assembly is quite sophisticated employing tough conduits, seals, coatings and high grade materials to insure that when you finally get around to applying the system that handful of times in your life, the cable hasn’t frozen. All of these protections and tortuous routing also influence the efficiency of the force transmission. A significant fraction of the force input to the system is consumed on the way back to the brake. These losses must be factored into the overall system capacity because the federal requirements limit the amount of force you can use to park. It is not at all uncommon to lose 30-50% of your force on the way back to the brake.

Once at the wheel, there are three types of brakes that are used to accomplish parking. Rear drum brake vehicles are the simplest. A drum brake is an extremely efficient brake and can multiply the “frictional torque” by factors of six and higher. By adding a lever inside the brake that allows the shoes to be spread mechanically, this brake can quickly and easily assume the duties of parking as well.

The situation is different for rear disc brakes. Two options exist. The first is the integrated caliper. This design relies on some additional components to allow application of the caliper piston by a mechanical input. While many design variations exist, virtually all rely on some form of lead screw that drills the piston out and back when pulled on by a lever. The output of a caliper brake is substantially lower than a drum brake. As a result, it is difficult to hold larger vehicles with this approach. Because of this, a hybrid approach is used on many larger rear disc vehicles.

These vehicles employ what is known as a “Drum in Hat Park Brake.” This uses a mini drum brake that is dedicated to only the parking function. Its drum is built into the hat section of the rear rotor. One significant advantage of the drum in hat is that the friction material used only has to accomplish parking function. Therefore is doesn’t have to also balance all the traditional needs of the friction materials such as squeal propensity, low wear, fade performance, dust etc. With these burdens removed it can be chosen almost exclusively on its static friction and much higher friction levels can be considered. This further reduces the size of the system.

In the service and repair world, the common issues are usually frozen or broken cables or the brake won’t hold. This is usually quickly identified when the brake is applied and goes full travel with minimal resistance. The usual culprit is the cables have stretched and the slack must be taken up.

In the service and repair world, the common issues are usually frozen or broken cables or the brake won’t hold. This is usually quickly identified when the brake is applied and goes full travel with minimal resistance. The usual culprit is the cables have stretched and the slack must be taken up.

Many systems have simple mechanisms to take up slack by tightening a nut on a long screw. If you’ve used up the range of adjustment, then it’s time for new cables.

Since the initial pretension must be set when the vehicle is built, some vehicle assemblers would prefer to not have this be an in-plant operation. Therefore, some park brake systems use a self-adjust system. These systems will not have any external adjustment and rely on a large clock spring in the pedal assembly. The spring is prewound when installed in the vehicle and then released when the system is full assembled. It behaves a lot like the take up on a tape measure. The spring does not completely unwind initially and retains enough capacity to continue to take up cable stretch over the life of the vehicle. If a cable is replaced or broken, the spring must be rewound prior to installation in order to re-achieve the appropriate pre-tension.

The other condition that is commonly seen in service, but is more difficult to diagnose is related to park brake drag. It is not uncommon to do a rear brake inspection and find the rear brakes with significant evidence of heat. Many times the park brake system should be considered as potential root cause. Over adjustment can be the cause, but in a great many cases it is driver error.

It is easy to let the brake get applied inadvertently only 1 or 2 clicks. Since no noticeable drag is felt, people drive on, and on, and on. Smoke, smell and noticeable drag will usually alert them eventually. This should set the red brake light, but it is surprisingly how often this is ignored. If it’s ignored on purpose, there is very little you can do. However, don’t assume they ignored it. In many vehicles the red light can be difficult to see and may be blocked by the steering wheel. This can be especially true for shorter drivers where their sightline through the wheel to the dash area can be much different than that for taller people.

Spending a moment with the person in their driver position and helping them understand the placement of the light and helping them consciously find it can be time well spent to prevent a return. While they will likely never admit they left the brake on to you, or whoever has to pay the repair bill, they probably won’t make the mistake again once it is brought to their attention.

As the voice of the public suggested in the beginning, the park brake system is an often overlooked, underutilized and under appreciated vehicle system. Like virtually every aspect of the vehicle, it is a highly engineered system with many subtle complications to manage to ensure it is present and accounted for when asked to perform. While that may an infrequent event for most of us, we’ll be grateful if the day comes that the primary brakes have failed and we go stabbing for that 4th pedal or lever as a last resort.