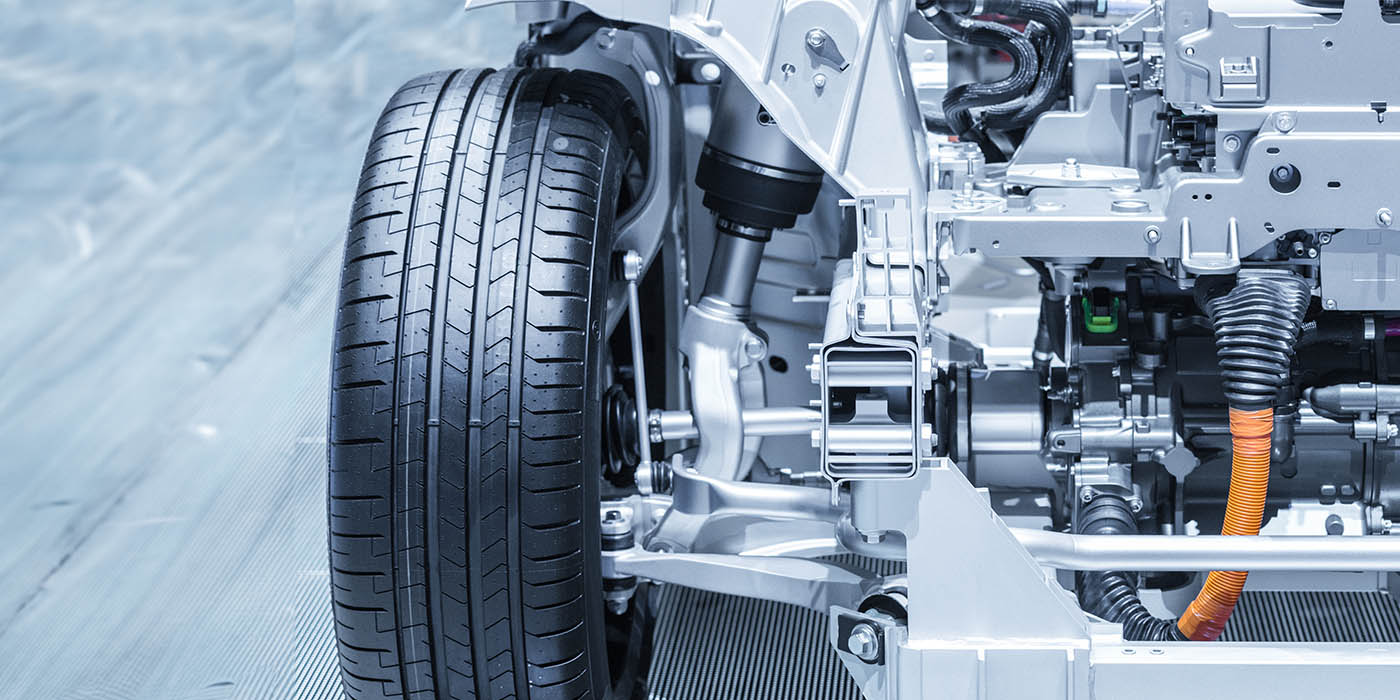

Rear-wheel drive has made a comeback on many large luxury import nameplates, but more than 80% of all cars on the road today are front-wheel drive. Most small- and mid-size cars are FWD, and all import minivans have FWD. What’s more, most of the full-size and crossover 4WD SUVs have halfshafts with CV joints front and rear, as do most of the all-wheel drive (AWD) cars. So there are lots of vehicles with CV joints and halfshafts that may be ripe for “getting the shaft.”

What we’re talking about is replacing CV joints and halfshafts. The potential market is estimated to be around 10 million shafts a year. According to Babcox Market Research, more than 90% of our readers service CV joints and shafts, and do an average of 8.3 jobs per month. The average job ticket is $190.65 — which tells us most of our readers are probably replacing only one shaft instead of both.

Talk about a missed service opportunity! Replacing only one shaft is like a dentist replacing only half of a set of dentures. If a CV joint on a high-mileage vehicle has failed, chances are its twin on the opposite side is also nearing the end of its service life.

The outer CV joints are usually the ones that most often need to be replaced for two reasons. One is that the outer CV joints wear more than the inner CV joints because of the steering angles they experience. The other is that the boots on the outer joints are more apt to fail than the ones on the inner joints.

A boot failure is bad news for any CV joint because it dooms the joint to premature failure. A split, cracked, loose or torn boot will throw grease, draining the joint of its vital supply of lubricant. Sooner or later, the joint will run dry, which is not a good thing for metal-to-metal surfaces that must withstand high-pressure loads and constant friction.

A boot that doesn’t seal can also allow outside contaminants such as road splash and dirt to enter the joint and wreak havoc on its precision-machined and polished surfaces. If the boot problem isn’t discovered almost immediately, joint failure will usually follow within a few thousand miles.

As long as a CV joint remains sealed inside its protective environment, it will do its job until it wears out. But real-world driving creates conditions that can cause bad things to happen to good boots. Age, heat, cold and road hazards can all conspire to breech the protective barrier provided by the boot around the joint. And once the seal is breached, trouble quickly follows. This is why you should always take the time to visually inspect the boots around both the inner and outer CV joints any time you are under a vehicle doing other maintenance or repairs.

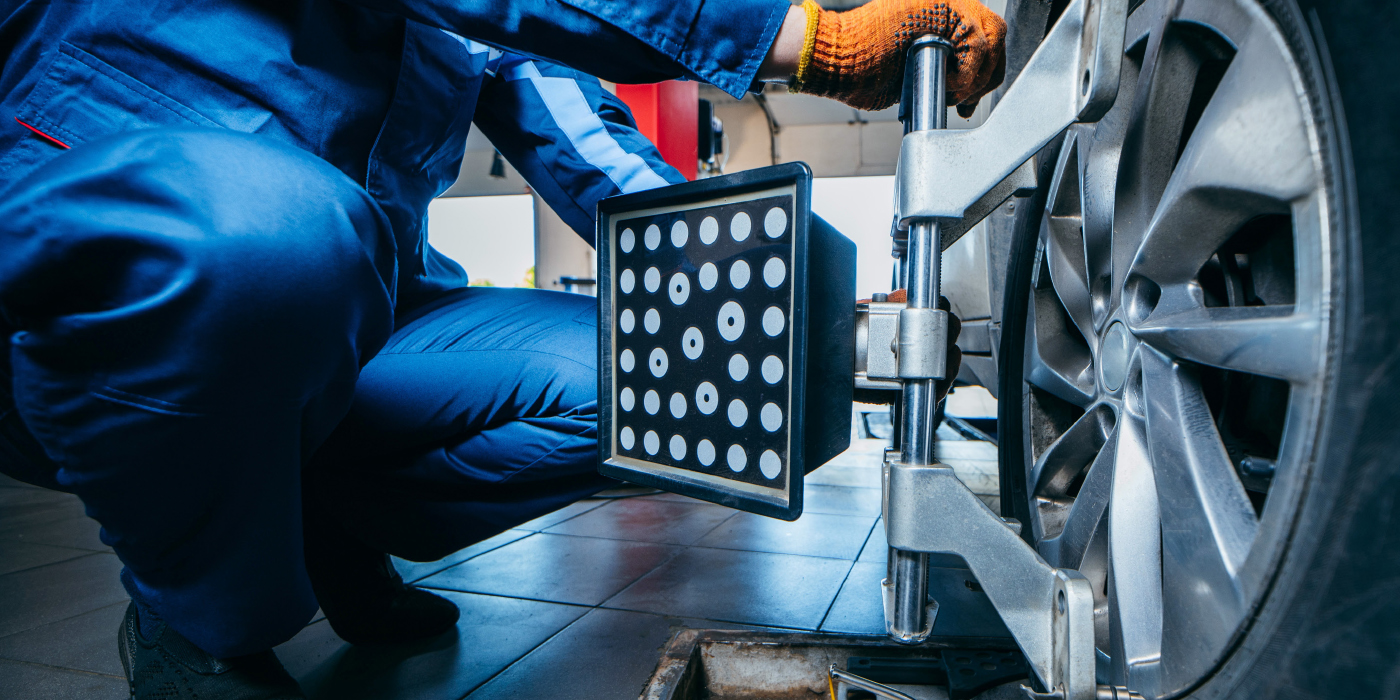

“Check the CV joint boots” should be a line item check off on every job ticket for every oil change, every brake job, every alignment job, every steering and suspension repair, and every exhaust repair. Seek and ye shall find. Then make your customer aware of the needed repairs and chances are you’ll usually make the sale.

FINDING FAULT

Under normal operating conditions, CV joints and boots are engineered to last upward of 150,000 miles. Some go the distance, but a lot reach the end of the road far short of their design life. According to one major aftermarket supplier of replacement shafts, CV joint shafts are typically being replaced at anywhere from 70,000 to 130,000 miles.

What’s more, some makes and models are notorious for eating shafts, one in particular because of the relatively thin case hardening that the carmaker uses in its CV joints.

BAD BOOTS

If you’re lucky and catch a bad boot before any contamination or damage to the CV joint has occurred, you may be able to save the joint. The first thing you need to do is to check the grease inside for contamination. If it feels gritty, the CV joint will have to be cleaned and inspected before the boot is replaced. If the CV joint has lost its grease and is making noise, you’re too late. The CV joint will have to be replaced.

It can be difficult to clean a CV joint while it’s still in the vehicle. There are aerosol solvents and similar products for this purpose, and cleaning in place obviously saves the labor of pulling the shaft. But the shaft will need to come out anyway if you’re replacing the damaged boot with a new one-piece boot. Split-boots are an option here, but these kinds of products are more for do-it-yourselfers who don’t have the tools or know-how to pull the shaft and replace the boot.

Most technicians won’t take a chance on installing a split boot for several reasons. One is that the CV joint may be contaminated and may soon fail anyway even if the boot is replaced. Better to replace the entire shaft assembly with a new or reman shaft. It’s faster, easier and reduces the risk of a comeback. Also, split boots may not seal properly if the glue or screws that hold the seam together are not installed correctly or the seam pulls loose.

A premium-quality one-piece boot is the best alternative for replacing a damaged OEM boot. Premium boots made of materials other than neoprene or hard plastic typically retain greater flexibility at cold temperatures (making them less apt to crack), and can also withstand higher temperatures.

JOINT INSPECTION

If you opt to replace a damaged boot, the CV joint should be removed from the shaft, disassembled and inspected for wear or damage. On most applications, the outer CV joint is held on the shaft by a snap ring or a lock ring, but some such as Honda and Toyota can be tricky to remove. And if you run into a tripod outer CV joint on an old Toyota Tercel or Nissan Sentra, disassembly is not possible. The entire shaft assembly must be replaced.

Rzeppa-style CV joints can be disassembled by tilting the inner race to one side and inserting a dowel or similar tool into the splines of the inner shaft. Tilt the race as far as it will go to one side to expose one of the balls. Remove the ball from its cage window with a small screwdriver. The inner race can then be tilted to the opposite side so the next ball can be removed, and so on until all the balls have been removed. The cage can now be rotated sideways to remove it and the inner race.

What to look for: nicks, gouges, cracks, spalling, roughness, flaking, etc. on the surface of the balls or tracks in the inner and outer races. The cage windows should also be inspected for dimples, wear or cracks. Each ball should fit snugly in its respective cage window because looseness here is often what causes the clicking or popping noises associated with a worn CV joint. Note: CV joints are precision-fit assemblies. The balls should be kept in order so they can be reassembled in the same grooves and cage windows as before. Each ball and track develop a unique wear pattern so don’t mix them up.

If the CV joint shows no unusual wear or damage, it is okay to reassemble and repack it with grease. Use the special CV grease provided with the replacement boot (never use any other type of grease!), and pack one-third of it into the joint and place the remainder in the boot. To install the boot, slip it onto the shaft (large end out). Then push the CV joint onto the shaft until it clicks in place or until the snap ring can be locked in place. Pull the outer lip of the boot over the CV joint housing so it lines up with the recess in the housing. Make sure the boot is not crimped, twisted or collapsed, then install the clamps. Some types of clamps require special tightening/crimping tools.

SYMPTOMS

Bad boots aren’t the only thing you need to look for. You also need to listen for noise or complaints that might indicate a CV joint problem. These include:

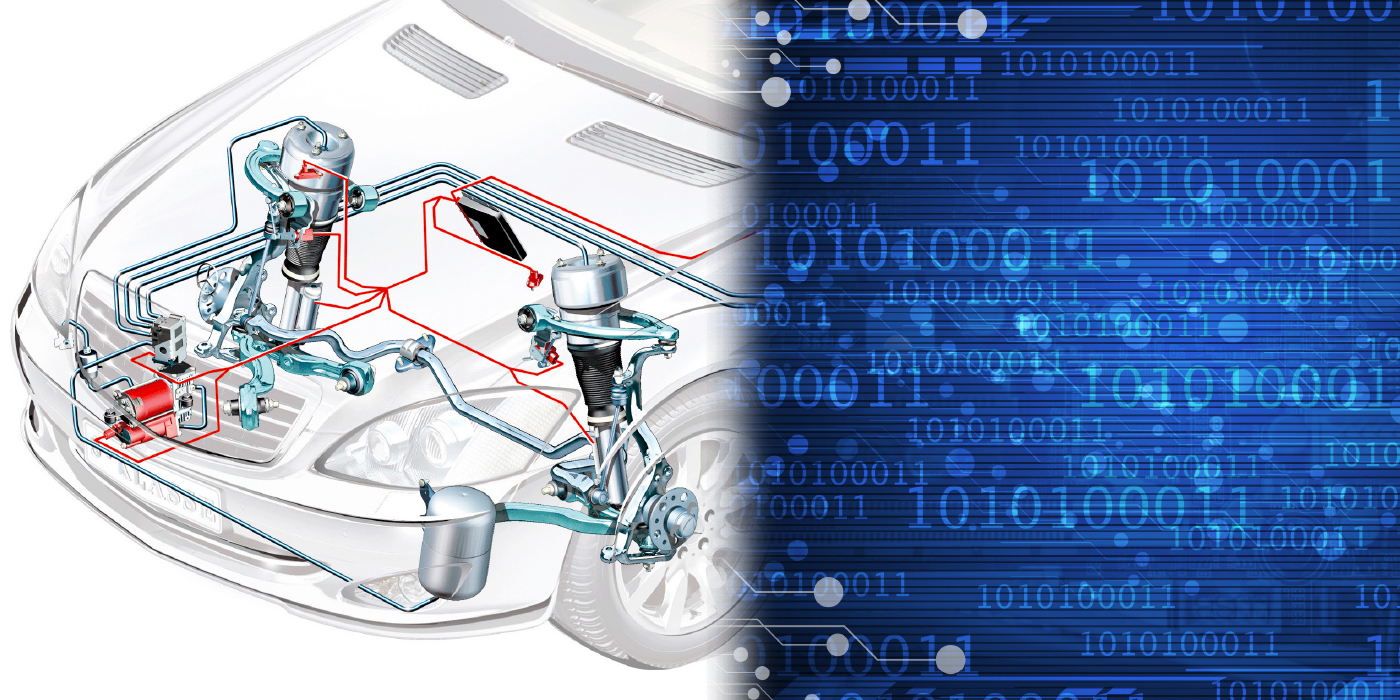

Popping or clicking noises when turning. This almost always indicates a worn or damaged outer CV joint. To verify this condition, place the vehicle in reverse, crank the steering wheel to one side and drive the vehicle backward in a circle (check the rearview mirror first!). If the noise gets louder, it confirms the diagnosis and the need for a new CV joint or replacement shaft assembly.

A “clunk” when accelerating, decelerating or when putting the transaxle into drive. The noise comes from excessive play in the inner joint on FWD applications, either inner or outer joints in a RWD independent suspension, or from the driveshaft CV joints or U-joint in a RWD or AWD powertrain. The same kind of noise can also be produced by excessive backlash in differential gears. To verify the condition, back the vehicle up, alternately accelerating and decelerating while in reverse. If the clunk or shudder is more pronounced, it confirms a bad inner joint.

A humming or growling noise. Sometimes due to inadequate lubrication in either the inner or outer CV joint, this symptom is more often due to worn or damaged wheel bearings, a bad intermediate shaft bearing on equal length halfshaft transaxles, or worn shaft bearings within the transaxle.

A shudder or vibration when accelerating. This may be caused by play in the inboard or outboard joints, but the most likely cause is a worn inboard plunge joint. Similar vibrations can also be caused by a bad intermediate shaft bearing on transaxles with equal length halfshafts, or by bad motor mounts on FWD vehicles with transverse-mounted engines.

A vibration that increases with speed. This symptom is rarely caused by a failing CV joint. An out-of-balance tire or wheel, an out-of-round tire or wheel, or a bent rim are the more likely causes.

REPLACEMENT TIPS

Since most technicians today opt to replace the entire shaft rather than individual CV joints, here are some suggestions that can help avoid comebacks:

Make sure you have the right replacement CV joint or shaft for the vehicle. Honda uses CV joints from various suppliers, so be sure the replacement joint has the same length, shaft diameter and spline count as the original.

When replacing the driveshafts on some cars, such as older Nissan Stanzas and Maximas, the halfshafts must be replaced in a certain order. On the older Nissans with an automatic transaxle, the right axle shaft must be removed first. Once the right axle has been pried out, insert a drift or screwdriver through the differential assembly to push out the left shaft. Then insert a bar into each side of the differential to prevent the side gears from slipping out of position.

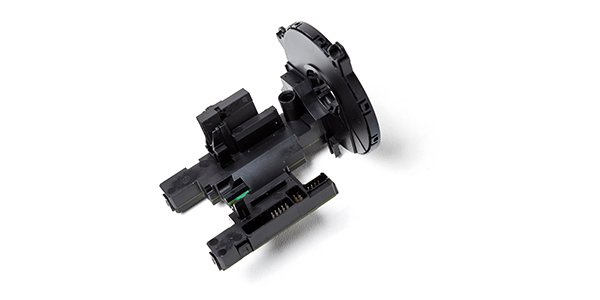

On all vehicles equipped with ABS, the tone ring for the front wheel speed sensors is often located on the outer CV joint housing. If the joint or driveshaft is being replaced, make sure the replacement has the proper tone ring. An air gap adjustment may also be required for the speed sensor. Use a nonmagnetic brass or plastic feeler gauge to set the speed sensor air gap to specs.

Check the transaxle oil seals for leaks before the driveshaft is replaced. If they need attention, now’s the time to fix them.

Replace the hub nut. Prevailing torque nuts lose their ability to stay tight once they are removed. The same goes for nuts that have to be staked in place. Most replacement shafts come with a new hub nut, but some new CV joints may not.

Use a torque wrench to tighten the ball joint and hub nut — never an impact wrench. Install new cotter pins and lock nuts if they’re used. Most manufacturers also recommend replacing any suspension nuts that were removed with new fasteners.

Test-drive the vehicle before returning it to your customer to avoid any last-minute surprises.