What does your shop do when a brake complaint due to noise enters the service bays? Is it a mark of shame for the technician that hurts their productivity for the rest of the day by randomly applying lubes, pastes and sprays to the brake system in hopes that the problem is at least temporarily solved?

Brake systems are complex and require an understanding of what is the root cause in generating the noise. Noisy brakes are not squeaking door hinges waiting to be lubed. You cannot simply apply a magic substance to make them quiet. It is not that using lubricants, pastes and sprays are not effective, it is simply intuitive that minimizing friction (without consideration of braking performance) using the most expedient available application is cost effective with respect to service labor.

The key to stopping brake noise is to do the brake job right the first time. If a customer does come back due to noise, a shop must have a diagnostic process to resolve the problem the first time.

The Interview

The first part of the brake noise diagnostic process is to interview the driver about the noise. Use the following questions and record the answers on the repair order:

Recreate the noise as best as possible. (If it is not clear what type of sound they are making, ask them if the noise is a groan, growl, chatter or squeal.)

How often does the noise occur? What speed(s)? What length of time?

What level of brake apply pressure causes the noise, light or hard?

Does the noise occur when cold or after the vehicle has been driven for a while?

Does the noise occur on a certain type of stop, like during a hill decent, high-speed braking or creeping in stop-and-go traffic?

Is there any pulsation in the brake pedal?

Does the pedal force become soft when continuously applied?

Using these questions in the interview process can eliminate miscommunication between the customer, service writer and the technician. With this information, the technician can replicate the noise quickly and come to a resolution sooner.

The next part of the diagnostic process is to understand how the noise is being generated. To do this we must understand the science of NVH.

NVH

The acronym NVH stands for Noise, Vibration and Harshness. It has been a term thrown around by engineers for the past three decades.

NVH is just as much of a study of the mechanical world as it is a study of human senses. The letters N and H, noise and harshness, in some ways refer to how human organs sense and interpret the outside world. Let’s say that you drop a pickle-fork ball-joint separator on the floor. As the fingers of the tool hit the floor, they start to vibrate. As the fingers vibrate, they excite the air around them.

The motion of the fingers pushes the air forward, compressing it and when the fingers pulls back, they suck the air back creating a low-pressure area. If you were to chart the pressure change over time, it would go up and down like a wave that would repeat itself (audible cyclic frequency) until the fingers of the pickle fork stopped vibrating. These changes in the air pressure of a sound wave eventually enter your ear because the vibration and associated frequency also move at a constant speed through the air. This transmission and conversion of vibrations of sound waves into mechanical vibration and then into nerve impulses is one of the cornerstones for understanding NVH and brake noise.

Let’s say you dropped a larger pickle-fork ball-joint separator with longer and larger fingers. If you dropped it from the same height, you would hear a different sound. The tone or sound would be lower in pitch and louder.

The reason for this is that the fingers of the fork are moving slower, taking more time to generate high- and low-pressure regions. The brain interprets this as a low or “bass” sound.

All sound waves dissipate or lose energy over a given distance. The closer you are to the source of a noise, the louder it will seem. A sound wave has two parts to a cycle. These are called the compression and rarefaction regions (high- and low-pressure areas). The number of times the cycle repeats in a second (previously referred to) is called the frequency and is measured in hertz.

You may have observed that the two different sizes of pickle forks vibrated at different rates due to their mass, material (associated with the degree of damping or energy dissipation) and shape. These structural and geometric characteristics define what “natural” frequencies of vibration will occur as well as the shape of vibration of the pickle forks or “vibration mode shapes.” Each natural frequency has a corresponding unique mode shape. This is why it is important to ask the customer to describe the brake noise so that you can classify it as low or high frequency.

The “sound pressure” or “loudness” is proportional to the “amplitude” (height) of the sound wave. In other words, how far the sound wave is able to push and pull the eardrum. The strength of a sound wave is dependent on the distance at which it is measured. Sound pressure is measured in decibels or dB.

The last letter in the acronym of NVH is Harshness. Certain frequencies cause stress, nervousness and fatigue (these are symptoms of annoyance) in people. This is a built in defense mechanism making us flee from what could be dangerous situation. These noises may include the cry of a baby or your mother-in-law’s voice. The term also is used in automotive suspension/chassis systems to describe shock/impulsive phenomena (e.g. impact harshness due to a pothole or bump in the road).

Noise Control

If you are trying to eliminate a noise, you could try to stop it from moving the air around it. To do this you could eliminate the air or get further away from it. This is not possible with brakes because they do not operate in a vacuum and they cannot be separated from the vehicle. You can suppress or eliminate the path of vibration transfer from the source leading to noise through damping and isolation methods or dissipate the noise by insulation/absorption treatment.

This effect can be observed by throwing a refrigerator magnet onto the vibrating pickle fork. The sound stops or is changed because the magnet added mass to the vibrating fingers and caused them to vibrate at a lower frequency, created increased damping at the natural frequency due to the mass, and shortened the time for the pickle fork to stop vibrating.

How All Brake Noise Starts

All brakes make noise. When the friction material makes contact with the rotor, the coupling causes the brake pad and rotor to oscillate and vibrate. In engineering terms, this is called “force coupled excitation,” which means that the components are locked as a combined system that will vibrate at the system’s natural frequency combined modes of vibration.

The amount of excitation and the frequency generated can be influenced by variations in brake torque (or changes in the coefficient of friction) across the rotor’s face. As the components heat up, the rotor may develop hot spots that could cause the rotor to have different regions of friction that produce different levels of brake torque. This friction coupling is where most brake noise is generated.

Looking at the Entire System

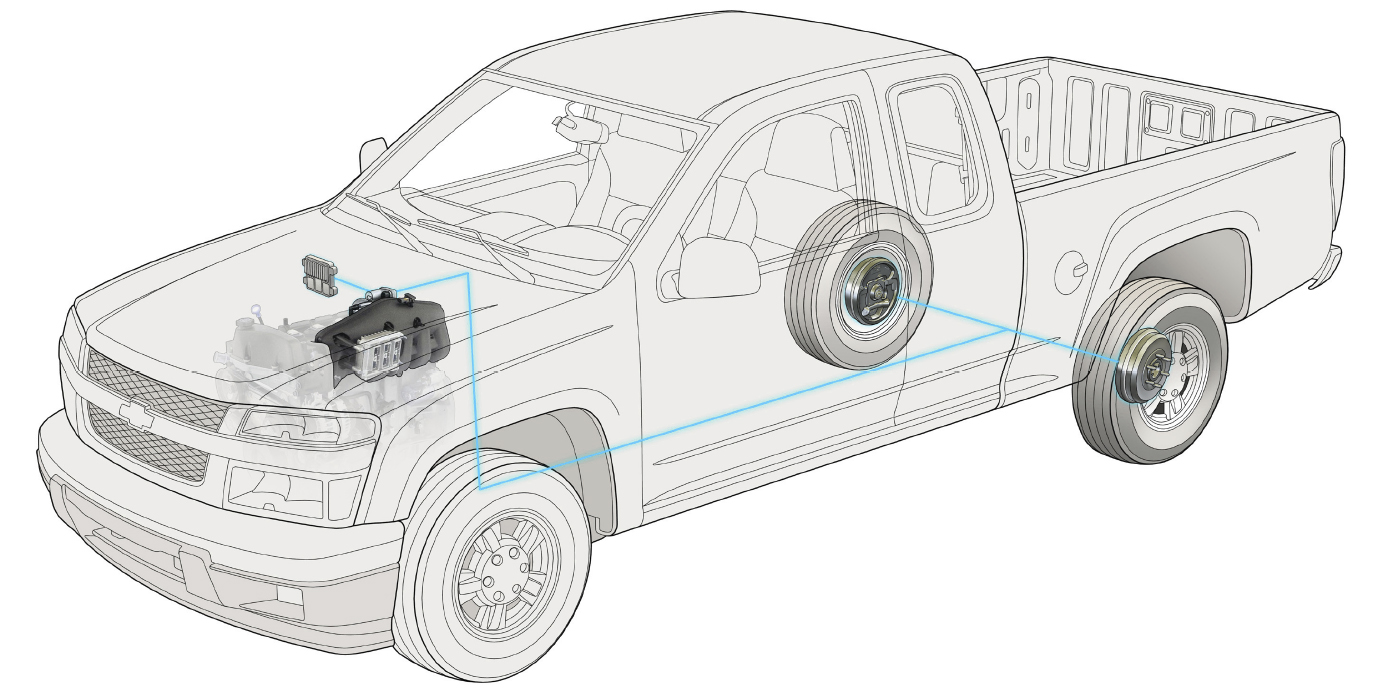

When a customer hears a brake noise, it is not just the “pure” sound of the friction coupling. The sound they are hearing is a product of the entire brake system, structural transfer paths through suspension components into the passenger compartment and amplified noise within the reflective wheel well acting as a reverberant echo chamber.

This is why it is important to look at the entire system when it comes to diagnosing brake noise. In the experiment with the ball-joint separator pickle forks, we observed that different components have different frequencies. The brake system also has different components with different masses, materials geometries and attachments (boundary conditions) all of which influence the natural frequencies and modeshapes.

At the aftermarket shop level, the vehicles that are serviced are each unique in terms of levels of wear and different part combinations. This mix of variables can make every brake noise complaint unique and not conform to normal brake noise scenarios in some cases. This is transparent and of no interest to the customer who always has the expectation that the vehicle should have quiet brakes. “Just fix it” is the bottom line.